Porn Play 🌽

How can an addiction to porn affect your real life?

Ani: Women are twice as likely to search for violent porn than men.

[...]

Liam: Maybe they just get so used to being treated like shit that they start to search it out. Like a Pavlovian dog thing.

Last week, I went to see one of the last showings of Porn Play at the Royal Court Theatre in London. It tells the story of 30 year old Ani, played by Ambika Mod (who is, very clearly, one of my faves). Ani’s a high flying academic and Milton aficionado (yes, John Milton of Paradise Lost), who is coming to terms with her addiction to porn and masturbation. Over time, her reliance on porn seeps into, and begins to destroy, her relationships, her sex life, her work…

I’ve been interested in the topic of porn addiction for a while. But, I’ll admit, most of my reading and thoughts on the topic have been about straight men: how it impacts them and their intimacy, and how they relate to women because of it. I actually hadn’t given much thought to women’s relationship with porn — beyond the role of women in porn, and the varying degrees of expectation from a partner. Growing up, I received mixed messages about porn. I feel like I was subconsciously hearing that, ‘It’s entirely good and normal for men to watch porn. But not for women, they get their kicks in other ways.’ As someone who enjoys reading erotica, I used my sample size of one to verify that message to be true.

I feel like Ani also receives a bunch of mixed messages. Her boyfriend is worried because he doesn’t think that ‘women had that dirty-pervert sex drive that men have’, whereas her best friend believes everyone is ‘weird about sex’ and porn is just normal ‘as long as it’s not animals or kids’. Then there’s her student who thinks her lectures glorify sexual violence. The mixed messages bring her shame about her consumption, initially. She feels rubbish when her boyfriend brings it up, she hides it when her dad walks in (and almost dies when he looks into her box of toys), and can barely tell her bestie what type of porn she watches nor how reliant she is on it. Her shame might be one of the reasons she begins to look for help — people are more likely to report an addiction if they believe there’s shame or some moral ill judgement attached to the behaviour. When I first started reading about porn addiction a few years ago, the scientific evidence seemed to suggest that you couldn’t get addicted to porn but it could be used compulsively — that it’s likely a control issue or an OCD-like struggle. Over time, I have started to understand why there’s apprehension to label over reliance on porn addiction — it could misdiagnose that shame or guilt. But the lack of an addiction diagnosis makes it hard to look for help. Where are you meant to go? Is it the GP, a therapist, or maybe something like the AA support group they show in the play?

Porn Play covers how ill equipped we are to have these conversations with friends, at school, with family, or with a gynaecologist, and leaves the audience with more uncomfortable questions than it has time to solve. I would be lying if I said it didn’t make me think about my own relationships. About wanting to discuss with a partner whether sex with me was enough or if they were thinking about porn. I thought about whether I should be chatting to friends more about their views on porn and its impact on real life. Real life… They talk so much in the first half of the show about porn not being real life. That it’s escapism. A bit of fun. A way to manage grief with pleasure, enable sleep, and quiet a busy mind. But where does on screen end and real life start? And when does watching become problematic? Is it when there’s an inability to enjoy intimacy or when you’re no longer able to be aroused without the visual of porn or when you can’t come without images of sexual violence to shock the system? Or is it when you want to play out a scenario on a partner without communicating it? Without spoiling it, there’s this scene where Ani wants to live out her fantasies. The porn she watches is clearly very violent but she fails to understand that IRL safe BDSM or role play is not as spontaneous as in porn — there has to be communication, guardrails, body safe toys, trust and education. She actually ends up in a dangerous situation and, although I think it was great how they slipped in some teachings about needing safe words, it was a hard watch.

The play did raise questions that I felt were quite controversial. For example, there was this whole conversation that tried to explain why Ani was into watching extreme violence against women: one of my fave characters, the AA guy, suggested that maybe it’s because in real life they’re both always trying to figure out how to save their mums. For him, it was watching his mum get hit at home and for Ani it was her mum’s battle with cancer. When you watch porn there’s no way to save the woman from the aggression: ‘You don’t have to worry about them,’ he says — and there’s some twisted pleasure in that. I didn’t buy it but I did buy that her heartbreak of losing her mum needed masking. It’s like scrolling TikTok for hours to numb the mind.

Ani is clearly brown. Not just in casting but also in name: Anisha Sandhu. In the play text there are a couple of references to her background which aren’t in the play. As a brown audience member though, I couldn’t help but watch through that lens. Not only do I feel it’s still rare to see brown bodies sexualised, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a brown character watch porn or masturbate on stage. Not even on screen, that I can think of?

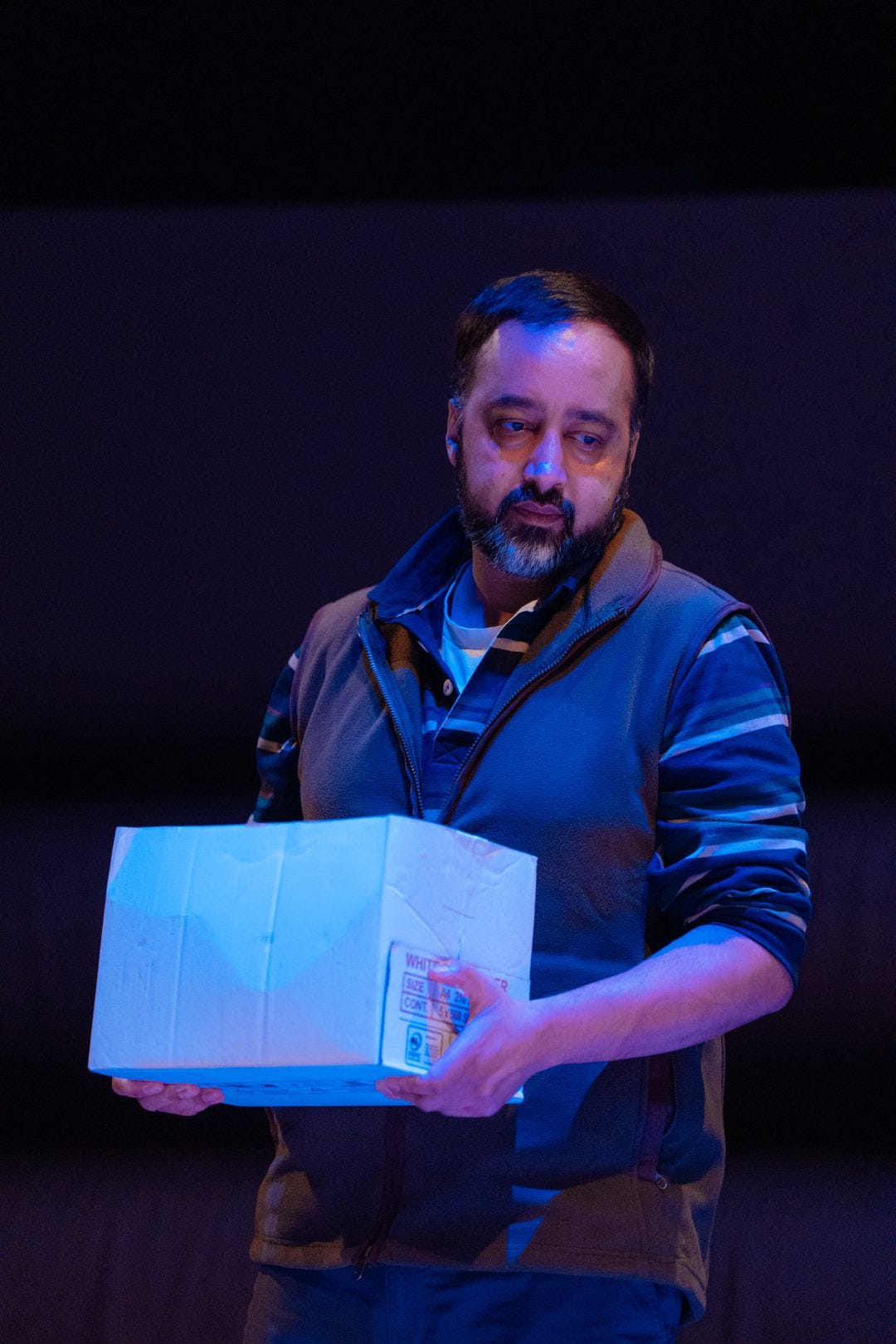

When addiction intertwines with being South Asian diaspora, does shame run higher? Is her silence louder for longer because of it? One of my favourite evolutions in the play is her relationship with her dad, a widower, who is played by British South Asian actor, Asif Khan. It feels cold. Like they don’t know how to talk to each other. And then, when she’s at her absolute worst (and, again, I don’t want to spoil it because I hear they might do another run), he does anything he can to help her. He understands the pleasure is actually masking the absolute devastation of her grief. It feels so brown dad stereotype coded. And I feel like that’s the only reason it works. I don’t think I would have understood that trajectory of the relationship without there being that cultural understanding.

I sat there at the end as people were filing out and wondered whether a show like this is enough for our communities to begin accepting that these things are happening inside our own homes too. That our kids and friends and family need help. As someone who has Opal because I have no will power when it comes to switching off of my phone, over-reliance on a digital world seems easier to me than it’s made out to be. Why would porn be any different?

Porn Play is written by Sophia Chetin-Leuner and directed by Josie Rourke.

Its run has currently ended but I reckon it might be back…

such an engaging read!! thank you for sharing