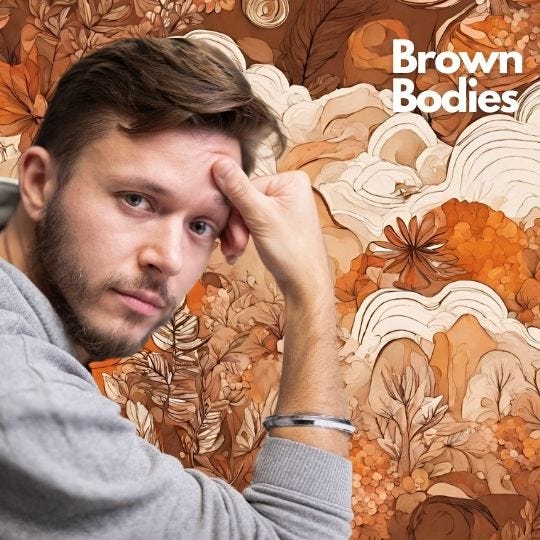

Sexuality can be both, not half

On becoming sexually liberated with Jassa Ahluwalia

Jassa Ahluwalia is an actor, filmmaker, presenter and the author of Both Not Half — part memoir, part research, the book explores what it means to be of mixed heritage. His mum is white English, his dad is a Brown Indian Punjabi, and he is both. And he is white. Or white presenting.

I first met Jassa at Eshaan Akbar’s 40th birthday. I happened to be listening to the audiobook version of Both Not Half at the time. I had that weird moment of, ‘Oh hey, I know so much about you, and your voice has been my gym buddy for the last month,’ and, of course, he didn’t know me from Adam. And then I embarrassed myself: I went to get my phone to show him I was legitimately listening to it — I wasn’t just saying it, OK!? — and I tripped over and smashed my phone. With a first impression like that, who could say no to an interview?

Did you have conversations about love and sex growing up? Did your parents have different approaches?

My dad was great but he didn’t really do conversations about anything to do with emotions. He was the action, the logistics, the planning. If I was ever in trouble he would sweep in and get it sorted. I tended to lean on my mum for my emotional wellbeing. There was an openness about love and sex at home but there were no demands or expectations. I feel fortunate that my parents created an environment where I could, largely, be myself.

My BG (grandma) did try and set me up on an arranged marriage date so that was probably the most explicit or serious conversation that was had about any sort of relationship!

Omg, how was that?

It came as a surprise. I never thought that that would be an experience that I would have. In a way, it was strangely validating that I was getting the ‘marriage conversation’ experience. It came at a time when I was first starting to question my identity and I was like, ‘Oh my God, I really am Punjabi. I really am Indian.’

So, did you meet the girl?

Yes! BG gave me her number and told us to arrange it. Initially, she had wanted it to be a ‘proper meeting’. You know, one where we invite her over for tea and all of that. But that was too much for me. I ended up going on the date without even seeing a photo. They did give me the option to but I just wanted to go in with an open mind. You never know, maybe it could’ve worked out!

I can’t believe you didn’t even look at a photo! OK, so there was no conflict at home when it came to dating…

The only conflict came from what I imposed upon myself when it came to dating South Asian women.

Growing up, I strongly associated my South Asian heritage with the familial. We’re brought up to see all Brown people as our brothers, sisters and cousins and so I didn’t find myself attracted to them. The first time I was attracted to a South Asian girl I was in my late teens and I didn’t know what to do with myself. It was terrifying and super exciting. It was almost like I had to rediscover my sexuality and attractions.

I’ve now had relationships with multiple women of South Asian heritage and I’m glad I was able to work through that as early as I did.

You speak Punjabi and are deeply involved with your culture. Yet you present as white. Do you find you get fetishised?

It's not a huge part of what I've experienced. I don't look mixed in the way mixed is fetishised. Normally, it’s light skinned Black and white. Although somebody did once describe me as ‘safely exotic’. Like, what do you do with that?

I have had comments on my Instagram saying, ‘Oh my God, a white guy my parents would approve of’ and similar.

Does it ever get any more racy than that?

Early on in my social media life I used to get… I actually don’t know what you call it… is there a female version of a dick pic? I think I’ve settled on ‘clit clicks’.

Is being with someone Sikh important to you?

Faith has never been a deciding factor of a relationship. I don't feel any strong feelings either way. Guru Nanak’s fundamental teaching is that there is a universal truth that expresses itself in many forms. Sikh teachings emerged in the context of Hindu and Islamic practices and the Guru Granth Sahib contains compositions written by spiritual masters of both traditions. What I do know is that I would never want to change my own spiritual practice nor would I want someone else to change theirs, as long as there was mutual understanding and respect.

What has, surprisingly, developed over the last few years — and since writing the book — is the depth and development of my own spiritual understanding. I had always thought of myself as maybe atheist and then maybe agnostic. Now, I find it important that people I date have a similar relationship or an understanding when it comes to the ineffable.

This applies to sex as well. Sex is a big part of the imagery and iconography of many Indian traditions. I come to really understand the potential to experience the Divine through that union. I’m only really starting to explore that stuff. I had an ex who had wanted to explore that but I was too early on in my own development to really open myself up to it — I look back on that and I’m like, ‘you idiot’.

Are you referring to Tantra?

In its broadest context, yes. Not just the purely physical bit that Western culture tends to fixate on.

Tantra is an ancient spiritual tradition that emphasises the union of consciousness (Shiva) and energy (Shakti) to find and recognise the divine in all aspects of life. It views sex as a sacred act and a potential path to spiritual awakening, not merely for pleasure. It can be a means to transcend the ego and unite with the divine.

In its holistic sense, I find it deeply fascinating and intriguing. It links with this idea I’ve come to understand from Vedantic tradition: You need to go inwards in order to be able to then exist outwardly. This is similar to a lot of Sikh philosophy which is about understanding the oneness and unity and realising the Divine within the self. But also understanding you need to take that outward to live in the world, not just inside yourself.

As you know, I read/listened to your book. There’s probably no surprise what my favourite chapter was: ‘Adventures in Masculinity’.

Obviously.

Obviously. When did you start questioning your ‘straightness’?

I think it's always been there at the back of my mind, maybe from my teens. I thought it was because I was a ridiculously horny teenager who made anything sexual. Just because the bus vibrated in a way that made me feel a particular way, that didn't mean I was into grinding on cars. That’s how I felt about men.

As I got older, there were definitely occasions where I was curious. I was genuinely curious about how it would feel to kiss a male co-star, for example. How would it be to be in bed with them? Would I learn something about myself?

At 23, a girl asked me if I’d ever thought about a threesome with a girl and another guy. I was simultaneously excited, disappointed and overwhelmingly turned on. Although nothing ever came of the proposition, the experience of how I felt was far too intense to ever forget.

In particular scenarios, the idea of physical intimacy with men felt exciting. We are taught that that means you’re not straight. But I also couldn’t imagine myself in a relationship with a guy. I put it down to it only being in moments of heightened arousal. But of course, that doesn’t diminish the validity of the feeling.

But, you know, the pressures of heteronormativity shut those curiosities down. I knew that the desires and attractions were there, but I didn't have the meta cognitive ability to reflect on what that meant. I didn't have a language to articulate what I was feeling. So it became a massive and complex deal in my head.

What changed?

I’ve been comfortably part of queer spaces for a long time through my work, my sister and friends. It’s a big part of why I failed to educate myself. I thought I got it. Like when my sister started to share her experiences as a queer woman, I thought I understood. Now, I know I didn't.

It was only when thinking about racial and ethnic identities in a non binary way that I began to unpick my relationship with binary thinking as a whole. I began to understand shame as a controlling societal force that had shackled me into a narrow version of straightness. I began to think about my sexuality. Basically, there came a moment where I decided I couldn’t be having another dream about sucking a dick — I decided to explore what it all meant for me.

What has exploration looked like for you?

Straight male sexuality doesn’t have much scope for exploration. Like sex toys, for example. Public perception is that interest in male sex toys is creepy, weird and almost sinister. I was first gifted one as a joke in 2015. It was one of those pocket pussies [Editor's note: This is a common male masturbator. They tend to mimic the sensation of a penis in a vagina. They tend to be smaller than something like a Fleshlight but, colloquially, people do use it to refer to Fleshlight sized stuff too]. It was a really shit one — it probably wasn’t made from body safe materials and left stains. I felt embarrassed when I was forced to admit I’d tried it. When I started consciously exploring, I got myself a proper one and omg it was fucking incredible.

Then, there was gay porn. Like many others, I had been scared of even looking up gay porn. There’s dicks in porn all the time so it’s not like it’s a million miles away from what I knew. There’s so much internalised homophobia and fear of rejection and emasculation when it comes to straight men watching gay porn. But I clicked on the gay section. I found some that interested me and even excited me. Some did nothing at all. My shame was shrinking the more I explored and I was beginning to open up to the full scope of my capacity for experience.

Talk to me about the Ninety/Ten theory.

Dr Ritch Savin-Williams wrote the book Mostly straight: sexual fluidity among men. He talks about those who identify as mostly straight: 90% straight, 10% gay. Comfortable with their sexuality, they don’t identify as bisexual but are aware of the potential to experience far more. They may also be romantically heterosexual but bi curious and sexually aroused by the same sex.

Dr Savin-Williams told me, after listening to my TEDx Talk, he thought maybe he should rename his book to Both Not Ninety/Ten, because a spectrum implies a binary exists. Sexuality is more fluid than binary. You can have multiplicity. Like, let’s be real, when you're exploring your 10%, you're not exploring at 10%, you're 100% percent exploring!

This is one of the things that freed me from fragile masculinity and has given me a more liberated version of straightness to live with.

Were you worried about putting that part of you out in public?

It felt like an absolute minor risk in the context of some of the shit that my sister — [the actor and writer] Ramanique Ahluwalia — has endured. My sister is queer. I have learnt a lot about sexual liberation because of her.

Finding a resolution for myself and being secure in who I am means it no longer feels scary to share.

I had so many messages when the book first came out, particularly from young South Asian men, saying how much they related to my experiences with sexuality. They said they’d never seen it articulated before. That’s heartening.

I don’t think anything I’m saying or doing is revolutionary. For example, when someone first told me about Feeld — the dating app for those looking to explore non traditional relationships like non-monogamy and polyamory. It offers diverse gender and sexual identity options too — I actually felt like I was really late to the party.

Do you think we’re going to see more South Asians in the diaspora having these conversations?

We're starting to see a lot more South Asian queer joy. And, invariably and as always, it’s the queer community that paves the way for people to feel comfortable in their own curiosities. Films like Joyland, podcasts like Brown Girls Do It Too, shows like The Gentlemen’s Club, this Substack…the conversations are happening.

We need to see more shedding of shame without also shaming those who are more conservative in their intimate lives. It can sometimes feel like there’s a pressure to be extremely open and adventurous, sexually, in a way that just isn't right for some people. We need to hold their needs and wants with as much respect. And the key is being able to communicate those wants and needs. This journey has taught me how to communicate far more clearly. I have found confidence to say quite clearly what I want and what my boundaries are. And sex is so much better for it.

You can find Jassa’s book, Both not Half, here.

*If you purchase the book through my Bookshop.org link, I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. You can also find the growing list of Brown Bodies reviewed and recommended books on there.